The Secrets of Sir Richard Kenworthy

Book 4 in the

Smythe-Smith Quartet

Sir Richard Kenworthy has less than a month to find a bride. He knows he can’t be too picky, but when he sees Iris Smythe-Smith hiding behind her cello at her family’s infamous musicale, he thinks he might have struck gold. She’s the type of girl you don’t notice until the second—or third—look, but there’s something about her, something simmering under the surface, and he knows she’s the one.

Iris Smythe–Smith is used to being underestimated. With her pale hair and quiet, sly wit she tends to blend into the background, and she likes it that way. So when Richard Kenworthy demands an introduction, she is suspicious. He flirts, he charms, he gives every impression of a man falling in love, but she can’t quite believe it’s all true. When his proposal of marriage turns into a compromising position that forces the issue, she can’t help thinking that he’s hiding something… even as her heart tells her to say yes.

From #1 New York Times bestselling author, and creator of the Bridgerton series, Julia Quinn presents the fourth and final installment in the Bridgerton adjacent Regency era-set world featuring the romantic adventures of the well-meaning but less-than-accomplished Smythe-Smith musicians. In this case, cellist Iris Smythe-Smith finds herself courted by a suspiciously eager nobleman—but is he only playing with her heartstrings?

Start Reading Now

Start Reading Now

Explore Inside this Story

Explore Inside this Story

Books in this series:

Find out more about the Smythe-Smith Quartet →

-

Quinn-tessential Quote

“Die!” the unicorn shrieked. “Die! Die! Die!”

-

Inside the Story:

JQ’s Author Notes- The concert that opens the story is the 1825 Smythe-Smith musicale, which makes it the same one that appears in It's in His Kiss. (Hence the later reference to the rakish Gareth St. Clair.) It also appears in the epilogues of Just Like Heaven, A Night Like This, and The Sum of All Kisses. And yes, it’s difficult to keep all the facts straight.

- The Shepherdess, the Unicorn, and Henry VIII was by far the most fun scene to write in the book. This disaster of a performance was first mentioned in It's in His Kiss, when Hyacinth and Gareth attend what they think will be a poetry reading. When I introduced the Pleinsworth girls in A Night Like This, and I realized that they were the ones who would have performed this play, it made it a breeze to create their characters. Harriet (the oldest) would be the playwright, and Frances (the youngest) would be obsessed with unicorns. Elizabeth (the middle child) would be the middle child. (I am also a middle child; read into that what you will.)

- Winston Bevelstoke makes an appearance in the early chapters of The Secrets of Sir Richard Kenworthy. Winston is one of my most popular secondary characters, having previously appeared in The Secret Diaries of Miss Miranda Cheever (brother of the hero) and What Happens in London (brother of the heroine). Readers ask for his story all the time. He’s not on the agenda for the next few books, but he is definitely on the radar.

Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. Portrait by Richard Rothwell. Public domain as per Wikipedia. - During the early part of the 19th century, the British Royal Family was more German than anything else. George III, who ruled from 1760-1820, was the first of the Hanoverian monarchs to be born in England and use English as his first language. George III married a German aristocrat, Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (yes, THAT Queen Charlotte!), and his son and heir, George IV, also married a German, Princess Caroline of Brunswick. (It was a spectacularly unhappy marriage, but that’s another story.) Queen Victoria’s first language was German, and it was most likely her only language during much of her early childhood. Her father, Prince Edward, died before her first birthday and she was raised primarily by her German-speaking mother, Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld.

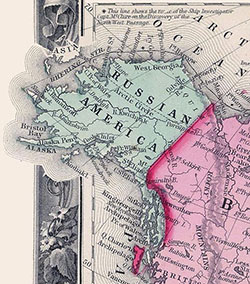

Public domain as per Wikipedia. - The Treaty of St. Petersburg got a mention mostly because I needed something Iris might have read about in the newspaper. The treaty defined the boundary between Russian America and the North Western Territory, or, as we would say today, between Alaska and Canada.

- Iris reads Mansfield Park in the carriage on her way north, later commenting that it’s much less romantic than Pride and Prejudice. I wrote the Afterword for the Signet Classic edition of Mansfield Park in 2008 and must concur with Iris. Fanny Price is no Lizzy Bennet! (To say nothing of Edmund Bertram and Mr. Darcy.)

- Maycliffe Park was modeled after Norton Conyers, a late medieval manor house in North Yorkshire. I later discovered that Norton Conyers was also the inspiration for Thornfield Hall, the home of Mr. Rochester in Jane Eyre. Charlotte Brontë visited Norton Conyers in 1839. There was already a legend of a madwoman locked in the attic; it’s certainly possible that Brontë heard the tale.

Bonus Features

Enjoy an Excerpt

from

The Secrets of Sir Richard Kenworthy

Chapter One

Pleinsworth House

London

Spring 1825

To quote that book his sister had read two dozen times, it was a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.

Sir Richard Kenworthy was not in possession of a fortune, but he was single. As for the wife…

Well, that was complicated.

“Want” wasn’t the right word. Who wanted a wife? Men in love, he supposed, but he wasn’t in love, had never been in love, and he didn’t anticipate falling in such anytime soon.

Not that he was fundamentally opposed to the idea. He just didn’t have time for it.

The wife, on the other hand…

He shifted uncomfortably in his seat, glancing down at the program in his hand.

You are Cordially Welcomed to

the 19th Annual Smythe-Smith Musicale

featuring a well-trained quartet of violin, violin, cello, and pianoforte

He had a bad feeling about this.

“Thank you, again, for accompanying me,” Winston Bevelstoke said to him.

Richard regarded his good friend with a skeptical expression. “I find it unsettling,” he remarked, “how often you’ve thanked me.”

“I’m known for my impeccable manners,” Winston said with a shrug. He’d always been a shrugger. In fact, most of Richard’s memories of him involved some sort of what-can-I-say shoulder motion.

“It doesn’t really matter if I forget to take my Latin exam. I’m a second son.” Shrug.

“The rowboat was already capsized by the time I arrived on the bank.” Shrug.

“As with all things in life, the best option is to blame my sister.” Shrug. (Also, evil grin.)

Richard had once been as unserious as Winston. In fact, he would very much like to be that unserious again.

But, as mentioned, he hadn’t time for that. He had two weeks. Three, he supposed. Four was the absolute limit.

“Do you know any of them?” he asked Winston.

“Any of who?”

Richard held up the program. “The musicians.”

Winston cleared his throat, his eyes sliding guiltily away. “I hesitate to call them musicians…”

Richard looked toward the performance area that had been set up in the Pleinsworth ballroom. “Do you know them?” he repeated. “Have you been introduced?” It was all well and good for Winston to make his customary cryptic comments, but Richard was here for a reason.

“The Smythe-Smith girls?” Winston shrugged. “Most of them. Let me see, who’s playing this year?” He looked down at his program. “Lady Sarah Prentice at the pianoforte–that’s odd, she’s married.”

Damn.

“It’s usually just the single ladies,” Winston explained. “They trot them out every year to perform. Once they’re married, they get to retire.”

Richard was aware of this. In fact, it was the primary reason he had agreed to attend. Not that anyone would have found this surprising. When a unmarried gentleman of twenty-seven reappeared in London after a three-year absence… One did not need to be a matchmaking mama to know what that meant.

He just hadn’t expected to be so rushed.

Frowning, he let his eyes fall on the pianoforte. It looked well-made. Expensive. Definitely nicer than the one he had back at Maycliffe Park.

“Who else?” Winston murmured, reading the elegantly printed names in the program. “Miss Daisy Smythe-Smith on violin. Oh, yes, I’ve met her. She’s dreadful.”

Double damn. “What’s wrong with her?” Richard asked.

“No sense of humor. Which wouldn’t be such a bad thing, it’s not as if everyone else is a barrel of laughs. It’s just that she’s so… obvious about it.”

“How is one obvious about a lack of humor?”

“I have no idea,” Winston admitted. “But she is. Very pretty, though. All blond bouncy curls and such.” He made a blond bouncy motion near his ear, which led Richard to wonder how it was possible that Winston’s hand movements were so clearly not brunette.

“Lady Harriet Pleinsworth, also on violin,” Winston continued. “I don’t believe we have been introduced. She must be Lady Sarah’s younger sister. Barely out of the schoolroom, if my memory serves. Can’t be much more than sixteen.”

Triple damn. Perhaps Richard should just leave now.

“And on the cello…” Winston slid his finger along the heavy stock of the program until he found the correct spot. “Miss Iris Smythe-Smith.”

“What’s wrong with her?” Richard asked. Because it seemed unlikely that there wouldn’t be something.

Winston shrugged. “Nothing. That I know of.”

Which meant that she probably yodeled in her spare time. When she wasn’t practicing taxidermy.

On crocodiles.

Richard used to be a lucky fellow. Really.

“She’s very pale,” Winston said.

Richard looked over at him. “Is that a flaw?”

“Of course not. It’s just…” Winston paused, his brow coming together in a little furrow of concentration. “Well, to be honest, that’s pretty much all I recall of her.”

Richard nodded slowly, his eyes settling on the cello, resting against its stand. It also looked expensive, although it wasn’t as if he knew anything about the manufacture of cellos.

“Why such curiosity?” Winston asked. “I know you’re keen to marry, but surely you can do better than a Smythe-Smith.”

Two weeks ago that might have been true.

“Besides, you need someone with a dowry, do you not?”

“We all need someone with a dowry,” Richard said darkly.

“True, true.” Winston might be the son of the Earl of Rudland, but he was the second son. He wasn’t going to inherit any spectacular fortunes. Not with a healthy older brother who had two sons of his own. “The Pleinsworth chit likely has ten thousand,” he said, looking back down at the program with an assessing glance. “But as I said, she’s quite young.”

Richard grimaced. Even he had limits.

“The florals–”

“The florals?” Richard interrupted.

“Iris and Daisy,” Winston explained. “Their sisters are Rose and Marigold and I can’t remember what else. Tulip? Bluebell? Hopefully not Chrysanthemum, poor thing.”

“My sister’s name is Fleur,” Richard felt compelled to mention.

“And a lovely girl she is,” Winston said, even though he had never met her.

“You were saying…” Richard prompted.

“I was? Oh, yes, I was. The florals. I’m not sure of their portions, but it can’t be much. I think there are five daughters in the family.” Winston’s lips twisted to one side as he considered this. “Maybe more.”

This didn’t necessarily mean that the dowries were small, Richard thought with more hope than anything else. He knew little of that branch of the Smythe-Smith family –he knew little of any branch, truth be told, except that once a year they all banded together, plucked four musicians from their midst, and hosted a concert that most of his friends were reluctant to attend.

“Take these,” Winston suddenly said, holding out two wads of cotton. “You’ll thank me later.”

Richard stared at him as if he’d gone mad.

“For your ears,” Winston clarified. “Trust me.”

“Trust me,” Richard echoed. “Coming from your lips, words to send a chill down my spine.”

“In this,” Winston said, stuffing his own ears with cotton, “I do not exaggerate.”

Richard glanced discreetly about the room. Winston was making no effort to hide his actions; surely it was considered rude to block one’s ears at a concert. But very few people seemed to notice him, and those who did wore expressions of envy, not censure.

Richard shrugged and followed suit.

“It’s a good thing you’re here,” Winston said, leaning in so that Richard could hear him through the cotton. “I’m not sure I could have borne it without fortification.”

“Fortification?”

“The pained company of beleaguered bachelors,” Winston quipped.

The pained company of beleaguered bachelors? Richard rolled his eyes. “God help you if you attempt to form sentences while intoxicated.”

“Oh, you’ll have that pleasure soon enough,” Winston returned, using his index finger to hold his coat pocket open just far enough to reveal a small metal flask.

Richard’s eyes widened. He was no prig, but even he knew better than to drink openly at a musical performance given by teenaged girls.

And then it began.

After a minute, Richard found himself adjusting the cotton in his ears. By the end of the first movement, he could feel a vein twitching painfully in his brow. But it was when they reached a long violin solo that the true gravity of his situation sank in.

“The flask,” he nearly gasped.

To his credit, Winston didn’t even smirk.

Richard took a long swig of what turned out to be mulled wine, but it did little to dull the pain. “Can we leave during intermission?” he whispered to Winston.

“There is no intermission.”

Richard stared at his program in horror. He was no musician, but surely the Smythe-Smiths had to know that what they were doing… that this so-called concert…

It was an assault against the very dignity of man.

According to the program, the four young ladies on the makeshift stage were playing a piano concerto by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. But to Richard’s mind, a piano concerto seemed to imply actual playing of a piano. The lady seated at that fine instrument was striking only half the required notes, if that. He could not see her face, but from the way she was hunched over the keys, she appeared to be a musician of great concentration.

Albeit not one of great skill.

“That’s the one with no sense of humor,” Winston said, motioning with his head toward one of the violinists.

Ah, Miss Daisy. She of the bouncing blond curls. Of all the performers, she was clearly the one who most considered herself a great musician. Her body dipped and swayed like the most proficient virtuoso as her bow flew across the strings. Her movements were almost mesmerizing, and Richard supposed that a deaf man might have described her as being one with the music.

Instead she was merely one with the din.

As for the other violinist… Was he the only one who could tell that she could not read music? She was looking anywhere but at her music stand, and she had not flipped a single page since the concert began. She’d spent the entire time chewing on her lip and casting frantic glances at Miss Daisy, trying to emulate her movements.

Which left the cellist. Richard felt his eyes settle on her as she drew her bow across the long strings of her instrument. It was extraordinarily difficult to pick out her playing underneath the frenetic sounds of the two violinists, but every now and then a low mournful note would escape the insanity, and Richard could not help but think—

She’s quite good.

He found himself fascinated by her, this small woman trying to hide behind a large cello. She, at least, knew how terrible they were. Her misery was acute, palpable. Every time she reached a pause in the score, she seemed to fold in on herself, as if she could squeeze down to nothingness and disappear with a “pop!”

This was Miss Iris Smythe-Smith, one of the florals. It seemed unfathomable that she might be related to the blissfully oblivious Daisy, who was still swiveling about with her violin.

Iris. It was a strange name for such a wisp of a girl. He’d always thought of irises as the most brilliant of flowers, all deep purples and blues. But this girl was so pale as to be almost colorless. Her hair was just a shade too red to be rightfully called blond, and yet strawberry blond wasn’t quite right, either. He couldn’t see her eyes from his spot halfway across the room, but with the rest of her coloring, they could not be anything but light.

She was the type of girl one would never notice.

And yet Richard could not take his eyes off her.

It was the concert, he told himself. Where else was he meant to look?

Besides, there was something soothing about keeping his gaze focused on a single unmoving spot. The music was so jarring he felt dizzy every time he looked away.

He almost chuckled. Miss Iris Smythe-Smith, she of the shimmering pale hair and too-large-for-her-body cello, had become his savior.

Richard Kenworthy didn’t believe in omens, but this one, he’d take.

Why was that man staring at her?

The musicale was torture enough, and Iris should know–this was the third time she’d been thrust onto the stage and forced to make a fool of herself in front of a carefully curated selection of London’s elite. It was always an interesting mix, the Smythe-Smith audience. First you had family, although in all fairness, they had to be divided into two distinct groups–the mothers and everyone else.

The mothers gazed upon the stage with beatific smiles, secure in their belief that their daughters’ display of exquisite musical talent made them the envy of all their peers. “So accomplished,” Iris’s mother trilled year after year. “So poised.”

So blind, was Iris’s unsaid response. So deaf.

As for the rest of the Smythe-Smiths –the men, generally, and most of the women who had already paid their dues on the altar of musical ineptitude– they grit their teeth and did their best to fill up the seats so as to limit the circle of mortification.

The family was marvelously fecund, however, and one day, Iris prayed, they would reach a size where they had to forbid the mothers from inviting anyone outside of family. “There just aren’t enough seats,” she could hear herself saying.

Unfortunately, she could also hear her mother asking her father’s man of affairs to inquire about renting a concert hall.

As for the rest of the attendees, quite a few of them came every year. A few, Iris suspected, did so out of kindness. Some surely came only to mock. And then there were the unsuspecting innocents, who clearly lived under rocks. At the bottom of the ocean.

On another planet.

Iris could not imagine how they could not have heard about the Smythe-Smith musicale, or more to the point, not been warned about it, but every year there were a few new miserable faces.

Like that man in the fifth row. Why was he staring at her?

She was quite certain she had never seen him before. He had dark hair, the kind that curled when it got too misty out, and his face had a finely sculpted elegance that was quite pleasing. He was handsome, she decided, although not terrifyingly so.

He was probably not titled. Iris’s mother had been very thorough in her daughters’ social educations. It was difficult to imagine there was an unmarried nobleman under the age of thirty that Iris and her sisters could not recognize by sight.

A baronet, maybe. Or a landed gentleman. He must be well-connected because she recognized his companion as the younger son of the Earl of Rudland. They had been introduced on several occasions, not that that meant anything other than the fact that the Hon. Mr. Bevelstoke could ask her to dance if he was so inclined.

Which he wasn’t.

Iris took no offense at this, or at least not much. She was rarely engaged for more than half the dances at any given assembly, and she liked having the opportunity to observe society in full swirl. She often wondered if the stars of the ton actually noticed what went on around them. If one was always at the eye of the proverbial storm, could one discern the slant of the rain, feel the bite of the wind?

Maybe she was a wallflower. There was no shame in that. Especially not if one enjoyed being a wallflower. Why, some of the—

“Iris,” someone hissed.

It was her cousin Sarah, leaning over from the pianoforte with an urgent expression on her face.

Oh, blast, she’d missed her entrance. “Sorry,” Iris muttered under her breath, even though no one could possibly hear her. She never missed her entrances. She didn’t care that the rest of the players were so mind-numbingly awful that it didn’t really matter if she came in on time or not–it was the principle of the matter.

Someone had to try to play properly.

She attended to her cello for the next few pages of the score, doing her best to block out Daisy, who was wandering all over the stage as she played. When Iris reached the next longish break in the cello part, however, she could not keep herself from looking up.

He was still watching her.

Did she have something on her dress? In her hair? Without thinking, she reached up to brush her coiffure, half expecting to dislodge a twig.

Nothing.

Now she was just angry. He was trying to rattle her. That could be the only explanation. What a rude boor. And an idiot. Did he really think he could possibly irritate her more than her own sister? It would take an accordion-playing minotaur to top Daisy on the scale of bothersome to seventh circle of hell.

“Iris!” Sarah hissed.

“Errrrgh,” Iris growled. She’d missed her entrance again. Although really, who was Sarah to complain? She’d skipped two entire pages in the second movement.

Iris located the correct spot in the score and leapt back in, relieved to note that they were nearing the end of the concerto. All she had to do was play her final notes, curtsy as if she meant it, and attempt to smile through the strained applause.

Then she could plead a headache and go home and shut her door and read a book and ignore Daisy and pretend that she wasn’t going to have to do it all over again next year.

Unless, of course, she got married.

It was the only escape. Every unmarried Smythe-Smith (of the female variety) had to play in the quartet when an opening at her chosen instrument arose, and she stayed there until she walked down a church aisle and claimed her groom.

Only one cousin had managed to marry before she was forced onto the stage. It had been a spectacular convergence of luck and cunning. Frederica Smythe-Smith, now Frederica Plum, had been trained on the violin, just like her older sister Eleanor.

But Eleanor had not “taken,” in the words of Iris’s mother. In fact, Eleanor had played in the quartet a record seven years before falling head over heels for a kindly curate who had the amazing good sense to love her with equal abandon. Iris rather liked Eleanor, even if she did fancy herself an accomplished musician. (She was not.)

As for Frederica… Eleanor’s delayed success on the marriage mart meant that the violinist’s chair was filled when her younger sister made her debut. And if Frederica just happened to make certain that she found a husband with all possible haste…

It was the stuff of legend. To Iris, at least.

Frederica now lived in the south of India, which Iris suspected was somehow related to her orchestral escape. No one in the family had seen her for years, although the occasional letter found its way to London, bearing news of heat and spice and the occasional elephant.

Iris hated hot weather and she wasn’t particularly fond of spicy food, but as she sat in her cousins’ ballroom, trying to pretend that fifty people weren’t watching her make a fool of herself, she couldn’t help but think that India sounded rather pleasant.

She had no opinion one way or the other on the elephants.

Maybe she could find herself a husband this year. Truth be told, she hadn’t really put in much of an effort the two years she’d been out. But it was so hard to make an effort when she was –and there was no denying it– so unnoticeable.

Except –she looked up, then immediately looked down– by that strange man in the fifth row. Why was he watching her?

It made no sense. And Iris hated –even more than she hated making a fool of herself– things that made no sense.

Chapter Two

It was clear to Richard that Iris Smythe-Smith planned to flee the concert the moment she was able. She wasn’t obvious about it, but he’d been watching her for nearly an hour; by this point, he was practically an expert on the expressions and mannerisms of the reluctant cellist.

He was going to have to act quickly.

“Introduce us,” Richard said to Winston, discreetly motioning toward her with his head.

“Really?”

Richard gave a curt nod.

Winston shrugged, obviously surprised by his friend’s interest in the colorless Miss Iris Smythe-Smith. But if he was curious, he did not show it past his initial query. Instead he maneuvered through the crowd in his usual smooth manner. The woman in question might have been standing awkwardly by the door, but her eyes were sharp, taking in the room, its inhabitants, and the interactions thereof.

She was timing her escape. Richard was sure of it.

But she was to be thwarted. Winston came to a halt in front of her before she could make her move. “Miss Smythe-Smith,” he said, everything good cheer and amiability. “What a delight to see you again.”

She bobbed a suspicious curtsy. Clearly she did not have the sort of acquaintance with Winston so as to warrant such a warm greeting. “Mr. Bevelstoke,” she murmured.

“May I introduce my good friend, Sir Richard Kenworthy?”

Richard bowed. “It is a pleasure to meet you,” he said.

“And you.”

Her eyes were just as light as he’d imagined, although with only the candlelight to illuminate her face, he could not discern their precise color. Gray, perhaps, or blue, framed by eyelashes so fair they might have been invisible if not for their astonishing length.

“My sister sends her regrets,” Winston said.

“Yes, she usually attends, doesn’t she?” Miss Smythe-Smith murmured with the merest hint of a smile. “She’s very kind.”

“Oh, I don’t know that kindness has anything to do with it,” Winston said genially.

Miss Smythe-Smith raised a pale brow and fixed a stare on Winston. “I rather think kindness has everything to do with it.”

Richard was inclined to agree. He could not imagine why else Winston’s sister would subject herself to such a performance more than once. And he rather admired Miss Smythe-Smith’s acuity on the matter.

“She sent me in her stead,” Winston went on. “She said it would not do for our family to be unrepresented this year.” He glanced over at Richard. “She was most firm about it.”

“Please do offer her my gratitude,” Miss Smythe-Smith said. “If you’ll excuse me, though, I must–”

“May I ask you a question?” Richard interrupted.

She froze, having already begun to twist toward the door. She looked at him with some surprise. So did Winston.

“Of course you may,” she murmured, her eyes not nearly as placid as her tone. She was a gently-bred young lady and he a baronet. She could offer no other response, and they both knew it.

“How long have you played the cello?” he blurted out. It was the first question that came to mind, and it was only after it had left his lips that he realized it was rather rude. She knew the quartet was terrible, and she knew that he must feel the same way. To inquire about her training was nothing but cruel. But he’d been under pressure. He couldn’t let her leave. Not without some conversation, at least.

“I–” She stammered for a moment, and Richard felt himself floundering inside. He hadn’t meant to– Oh, bloody hell.

“It was a lovely performance,” Winston said, looking as if he’d like to kick him.

Richard spoke quickly, eager to rehabilitate himself in her eyes. “What I meant was that you seemed somewhat more proficient than your cousins.”

She blinked several times. Bloody hell, now he’d gone and insulted her cousins, but he supposed better them than her.

He plowed on. “I was seated near to your side of the room, and occasionally I could hear the cello apart from the other instruments.”

“I see,” she said slowly, and perhaps somewhat warily. She did not know what to make of his interest, that much was clear.

“You’re quite skilled,” he said.

Winston looked at him in disbelief. Richard could well imagine why. It hadn’t been easy to discern the notes of the cello through the din, and to the untrained ear, Iris must have seemed just as dreadful as the rest. For Richard to say otherwise must seem the worst sort of false flattery.

Except that Miss Smythe-Smith knew that she was a better musician than her cousins. He’d seen it in her eyes as she reacted to his statement. “We have all studied since we were quite young,” she said.

“Of course,” he replied. Of course that would be what she’d say. She wasn’t about to insult her family in front of a stranger.

An awkward silence descended upon the trio, and Miss Smythe-Smith made that polite smile again, with the clear intention of excusing herself.

“The violinist is your sister?” Richard asked, before she could speak.

Winston shot him a curious look.

“One of them, yes,” she replied. “The blond one.”

“Your younger sister?”

“By four years, yes,” she said, her voice sharpening. “This is her first season, although she did play in the quartet last year.”

“Speaking of that,” Winston put in, thankfully saving Richard from having to think up another exit-preventing question, “why was Lady Sarah seated at the pianoforte? I thought the quartet was for unmarried ladies only.”

“We lack a pianist,” she answered. “If Sarah had not stepped up, the concert would have been canceled.”

The obvious question hung in the air. Would that have been such a bad thing?

“It would have broken my mother’s heart,” Miss Smythe-Smith said, and it was impossible to tell just what emotion colored her voice. “And those of my aunts.”

“How very kind of her to lend her talents,” Richard said.

And then Miss Smythe-Smith said the most astonishing thing. She muttered, “She owed us.”

Richard started. “I beg your pardon?”

“Nothing,” she said, smiling brightly… and falsely.

“No, I must insist,” Richard said, intrigued. “You cannot make such a statement and leave it unclarified.”

Her eyes flitted to the left. Maybe she was making sure her family could not hear. Or maybe she was simply trying not to roll her eyes completely. “It is nothing, really. She did not play last year. She withdrew on the day of the performance.”

“Was the concert canceled?” Winston asked, brow furrowed as he tried to recall.

“No. Her sisters’ governess stepped in.”

“Oh, right,” Winston said with a nod. “I remember. Jolly good of her. Remarkable, really, that she knew the piece.”

“Was your cousin ill?” Richard inquired.

Miss Smythe-Smith opened her mouth to speak, and then at the last moment changed her mind about what she was going to say. Richard was sure of it.

“Yes,” she said simply. “She was quite ill. Now if you will excuse me, I’m afraid there is a matter I must attend to.”

She curtsied, they bowed, and she departed.

“What was that about?” Winston asked immediately.

“What?” Richard countered, feigning ignorance.

“You practically threw yourself in front of the door to prevent her from leaving.”

Richard shrugged. “I found her interesting.”

“Her?” Winston looked toward the door through which Miss Smythe-Smith had just exited. “Why?”

“I don’t know,” Richard lied.

Winston turned to Richard, then back to the door, and then back to Richard again. “I must say, she’s not your usual type.”

“No,” Richard said, even though he’d never thought of his preferences in those terms. “No, she’s not.”

But then again, he’d never needed to find himself a wife. In two weeks, no less.

The following day found Iris trapped in the drawing room with her mother and Daisy, waiting for the inevitable trickle of callers. They had to be at home for visitors, her mother insisted. People would want to congratulate them on their performance.

Her married sisters would stop by, Iris imagined, and most likely a few other ladies. The same ones who attended each year out of kindness. The rest would avoid the Smythe-Smith home –any of the Smythe-Smith homes– like the proverbial plague. The last thing anyone wanted to do was make polite conversation about an aural disaster.

It was rather as if the Dover cliffs crumbled into the sea, and everyone sat about drinking tea, saying, “Oh yes, ripping good show. Too bad about the vicar’s house, though.”

But it was early still, and they had not yet been graced by a visitor. Iris had brought down something to read, but Daisy was still aglow with delight and triumph.

“I thought we were splendid,” she announced.

Iris lifted her eyes from her book just long enough to say, “We weren’t splendid.”

“Perhaps you weren’t, hiding behind your cello, but I have never felt so alive and in tune with the music.”

Iris bit her lip. There were so very many ways she could respond. It was as if her younger sister was begging her to use every sarcastic word in her arsenal. But she held her tongue. The concert always left her feeling irritable, and no matter how annoying Daisy was –and she was, oh, she was– it wasn’t her fault that Iris was in such a bad mood. Well, not entirely.

“There were so many handsome gentlemen at the performance last night,” Daisy said. “Did you see, Mama?”

Iris rolled her eyes. Of course their mother had seen. It was her job to notice every eligible gentleman in the room. No, it was more than that. It was her vocation.

“Mr. St. Clair was there,” Daisy said. “He’s so very dashing with his queue.”

“He’ll never look twice at you,” Iris said.

“Don’t be unkind, Iris,” their mother scolded. But then she turned to Daisy. “But she’s right. And nor would we wish him to. He’s far too rakish for a proper young lady.”

“He was talking with Hyacinth Bridgerton,” Daisy pointed out.

Iris swung her glance over to her mother, eager –and, truth be told, amused– to see how she’d respond to that. Families didn’t get more popular or respectable than the Bridgertons, even if Hyacinth –the youngest– was known as something of a terror.

Mrs. Smythe-Smith did what she always did when she did not wish to reply. Her brows rose, her chin dipped, and she gave a disdainful sniff.

Conversation over. At least that particular thread.

“Winston Bevelstoke isn’t a rake,” Daisy said, tacking a bit to the right. “He was seated near the front.”

Iris snorted.

“He’s gorgeous!”

“I never said that he wasn’t,” Iris replied. “But he must be nearly thirty. And he was in the fifth row.”

That seemed to mystify their mother. “The fifth–”

“It’s certainly not the front,” Iris cut in. Blast it all, she hated when people got the little details wrong.

“Oh, for heaven’s sake,” Daisy said, “It doesn’t matter where he was sitting. All that matters is that he was there.”

This was correct, but still, so clearly not the salient point. “Winston Bevelstoke would never be interested in a girl of seventeen,” Iris said.

“Why wouldn’t he be?” Daisy demanded. “I think you’re jealous.”

Iris rolled her eyes. “That is so far from the truth I can’t even begin to say.”

“He was watching me,” Daisy insisted. “That he is as yet unmarried speaks to his selectiveness. Perhaps he has simply been waiting for the perfect young lady to come along.”

Iris took a breath, quelling the retort tickling at her lips. “If you marry Winston Bevelstoke,” she said calmly, “I shall be the first to congratulate you.”

Daisy’s eyes narrowed. “She’s being sarcastic again, Mama.”

“Don’t be sarcastic, Iris,” Maria Smythe-Smythe said, never taking her eyes from her embroidery.

Iris scowled at her mother’s rote scolding.

“Who was that gentleman with Mr. Bevelstoke last night?” Mrs. Smythe-Smith asked. “The one with the dark hair.”

“He was talking to Iris,” Daisy said, “after the performance.”

Mrs. Smythe- Smith fixed a shrewd stare upon Iris. “I know.”

“His name is Sir Richard Kenworthy,” Iris said.

Her mother’s brows rose.

“I’m sure he was being polite,” Iris said.

“He was being polite for a very long time,” Daisy giggled.

Iris looked at her in disbelief. “We spoke for five minutes. If that.”

“It’s more time than most gentleman talk to you.”

“Daisy, don’t be unkind,” their mother said, “but I must agree. I do think it was more than five minutes.”

“It wasn’t,” Iris muttered.

Her mother did not hear her. Or more likely, chose to ignore. “We shall have to find out more about him.”

Iris’s mouth opened into an indignant oval. Five minutes she’d spent in Sir Richard’s company, and her mother was already plotting the poor man’s demise.

“You’re not getting any younger,” Mrs. Smythe-Smith said.

Daisy smirked.

“Fine,” Iris said. “I shall attempt to capture his interest for a full quarter of an hour next time. That ought to be enough to send for a special license.”

“Oh, do you think so?” Daisy asked. “That would be so romantic.”

Iris could only stare. Now Daisy missed the sarcasm?

“Anyone can be married in a church,” Daisy said. “But a special license is special.”

“Hence the name,” Iris muttered.

“They cost a terrific amount of money,” Daisy continued, “and they don’t give them out to just anybody.”

“Your sisters were all properly married in church,” their mother said, “and so shall you be.”

That put an end to the conversation for at least five seconds. Which was about how long Daisy could manage to sit in silence. “What are you reading?” she asked, craning her neck toward Iris.

“Pride and Prejudice,” Iris replied. She didn’t look up, but she did mark her spot with her finger. Just in case.

“Haven’t you read that before?”

“It’s a good book.”

“How can a book be good enough to read twice?”

Iris shrugged, which a less obtuse person would have interpreted as a signal that she did not wish to continue the conversation.

But not Daisy. “I’ve read it, too, you know,” she said.

“Have you?”

“Quite honestly, I didn’t think it was very good.”

At that, Iris finally raised her eyes. “I beg your pardon.”

“It’s very unrealistic,” Daisy opined. “Am I really expected to believe that Miss Elizabeth would refuse Mr. Darcy’s proposal of marriage?”

“Who is Miss Elizabeth?” Mrs. Smythe-Smith asked, her attention finally wrenched from her embroidery. She looked from daughter to daughter. “And for that matter, who is Mr. Darcy?”

“It was patently clear that she would never get a better offer than Mr. Darcy,” Daisy continued.

“That’s what Mr. Collins said when he proposed to her,” Iris shot back. “And then Mr. Darcy asked her.”

“Who is Mr. Collins?”

“They are fictional characters, Mama,” Iris said.

“Very foolish ones, if you ask me,” Daisy said haughtily. “Mr. Darcy is very rich. And Miss Elizabeth has no dowry to speak of. That he condescended to propose to her–”

“He loved her!”

“Of course he did,” Daisy said peevishly. “There can be no other reason he would ask her to marry him. And then for her to refuse!”

“She had her reasons.”

Daisy rolled her eyes. “She’s just lucky he asked her again. That’s all I have to say on the matter.”

“I think I ought to read this book,” Mrs. Smythe-Smith said.

“Here,” Iris said, feeling suddenly dejected. She held the book out toward her mother. “You can read my copy.”

“But you’re in the middle.”

“I’ve read it before.”

Mrs. Smythe-Smith took the book, flipped to the first page and read the first sentence, which Iris knew by heart.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.

“Well, that’s certainly true,” Mrs. Smythe-Smith said to herself.

Iris sighed, wondering how she might occupy herself now. She supposed she could fetch another book, but she was too comfortable slouched on the sofa to consider getting up. She sighed.

“What?” Daisy demanded.

“Nothing.”

“You sighed.”

Iris fought the urge to groan. “Not every sigh has to do with you.”

Daisy sniffed and turned away.

Iris closed her eyes. Maybe she could take a nap. She hadn’t slept very well the night before. She never did, the night after the musicale. She always told herself she would, now that she had another whole year before she had to start dreading it again.

But sleep was not her friend, not when she couldn’t stop her brain from replaying every last moment, every botched note. The looks of derision, of pity, of shock and surprise… She supposed she could almost forgive her cousin Sarah for feigning illness the year before to avoid playing. She understood. Heaven help her, no one understood better than she.

And then Sir Richard Kenworthy had demanded an audience. What had that been about? Iris was not so foolish to think that he was interested in her. She was no diamond of the first water. She fully expected to marry one day, but when it happened, it wasn’t going to be because some gentleman took one look at her and fell under her spell.

She had no spells. According to Daisy, she didn’t even have eyelashes.

No, when Iris married, it would be a sensible proposition. An ordinary gentleman would find her agreeable and decide that the granddaughter of an earl was an advantageous thing to have in the family, even with her modest dowry.

And she did have eyelashes, she thought grumpily. They were just very pale.

She needed to find out more about Sir Richard. But more importantly, she needed to figure out how to do that without attracting attention. It wouldn’t do to be seen as chasing after him. Especially when—

“Callers, ma’am,” their butler announced.

Iris sat up. Time for good posture, she thought with false brightness. Shoulders up, back straight…

“Mr. Winston Bevelstoke,” the butler intoned.

Daisy straightened and preened, but not before tossing an I-told-you-so glance at Iris.

“And Sir Richard Kenworthy.”

The Secrets of Sir Richard Kenworthy

by Julia Quinn

is available in the following formats:

Mass Market Paperback:

En Español

Not ready to order yours? Check out this story's overview. Read the excerpt. Listen to a bit on audio. Find out more about the series. There’s so much to love!

Awards & Achievements

- The Secrets of Sir Richard Kenworthy was a finalist in the 2016 Audie awards for best romance audiobook. Congratulations to narrator Rosalyn Landor!

-

The Secrets of Sir Richard Kenworthy was a finalist in the 2016 RITA Awards in the Short Historical category. The RITAs are awarded by Romance Writers of America and are the highest honor in romance writing. The eventual winner was It Started With a Scandal by Julie Anne Long.

The Secrets of Sir Richard Kenworthy was a finalist in the 2016 RITA Awards in the Short Historical category. The RITAs are awarded by Romance Writers of America and are the highest honor in romance writing. The eventual winner was It Started With a Scandal by Julie Anne Long. - Four weeks on the USA Today list, peaking at #9.

-

The Secrets of Sir Richard Kenworthy debuted at #2 on the New York Times print bestseller list for the week of February 15, 2015.

The Secrets of Sir Richard Kenworthy debuted at #2 on the New York Times print bestseller list for the week of February 15, 2015.